On the invitation of Government Architect Jo Coenen, four teams have spent recent months drawing up proposals for the Delta Metropolis. Monday December 9 saw the presentation of the four proposals for the area ‘formerly known as’ Randstad.

Above: OMA scheme

Below: the metropolises of north-west Europe (below-right a night-time satellite photo on which the Delta conurbation is clearly visible)

The proposal by OMA deserves serious consideration before the policy memorandum is finalised and the Delta Metropolis is added to the planning map. The scheme negates the myth of the Randstad as a pure entity (an urbanised ring enclosing green space), with an assumed identity of its own, that can develop autonomously. As we are accustomed to from OMA, Floris Alkemade began his presentation with an image of the world and then zoomed in on the larger conurbation (Randstad, Ruhr Area, northern flank of Belgium as far as Lille) of which the Delta Metropolis forms a part. This much larger entity is the true Delta Metropolis, since it is entirely focused and dependent on the Rhine and Meuse deltas from which the Delta Metropolis derives its name. In contrast to familiar metropolitan regions like London, Paris and New York, this larger conurbation has a fragmentary character. It lacks a centre – or ‘hollow core’ as Alkemade calls it – but that might just be the very identity worth stimulating. Searching a centre or new identity is futile. So why not go with the flow of current development?

Looking again at the west of the Netherlands from this larger perspective, we see that artificially reinforcing the unity of the entire Randstad is equally futile. A better starting point, claims Alkemade, would be two major, mutually stimulating and competing poles: the ‘centre city’ of Amsterdam and a new ‘field, grid or pixel city’ incorporating The Hague and Rotterdam (with a secondary line of development focused on strengthening older towns along the Rhine like Leiden and Utrecht. Amsterdam has its own identity and is developing perfectly well on its own. But the Randstad’s southern flank is grappling with stagnation and needs fresh development impetus. The proposal takes into account existing and recently initiated development in the zone extending from The Hague to Rotterdam. By laying a rectilinear grid over this area and designating it a ‘city’, we can create a logic for further development, the most significant new element of which is the conversion of the A13 motorway into a central urban boulevard. This is not a new idea, but Alkemade incorporates the A13 Boulevard into a comprehensive vision for the Delta Metropolis and convincingly makes a case for reconstructing the A13. This makes it an almost certain element of the Policy Memorandum on Space.

What now? The three Dutch proposals could be stitched together to form a new Randstad, which could then perhaps be called Delta Metropolis. Sijmons develops the Green Heart, Teun Koolhaas develops the Haarlemmermeer-Amsterdam-Almere-Utrecht band in collaboration with Amsterdam’s department of physical planning, and OMA develops a vision for the new Delta City (The Hague / Rotterdam).

All this, however, is entirely dependent on political will, and in particular on the forthcoming Policy Memorandum on Space. Will One Architecture, which steered clear of the limelight during the Design Workshop, continue to play a co-ordinating or design role? Will Government Architect Jo Coenen continue to promote the Snozzi scheme? Will the Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment – together with the other ministries and the Government Architect Office (overall co-ordinator of the Big Projects and thus of the Delta Metropolis) – ever complete the Policy Memorandum? And will the forthcoming national election produce a strong cabinet willing to take decisive action. We’ll have to wait and see, but the wait must not and should not take too long.

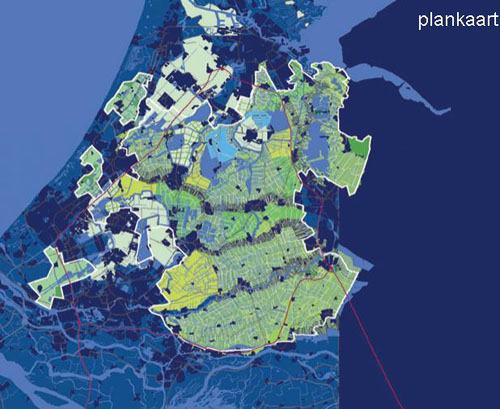

TKA scheme

And then there is the urbanised area of this hypothetical metropolis. Teun Koolhaas, who looked at the northern flank, presented a plan (a series of part-plans actually) that seemed to address the theme of how to shape society in a rather touching manner. In a presentation that gathered steam in a somewhat halting fashion, his enthusiasm for his designs appeared to grow in an infectious manner. The number of part-plans that comprised his proposal was, he said, calculated to account for the inevitable process of deletion. ‘Better to propose too much than too little, since a portion will always get scrapped.’ His way of working – layered development of part-plans based on an all-encompassing concept, but each with a separate identity – is probably the most ‘feasible’ and least ‘dangerous’. It’s also closest to the tradition of planning in the Randstad, can be easily combined with Sijmons’ water project for the Green Heart, and would therefore seem the most obvious basis for a comprehensive vision for the Delta Metropolis. Which is not to say that this is the best design.

Gardening in the Green Heart, design H+N+S

The other proposals were far more pragmatic and planning-oriented, but visually imaginative all the same. Under the title ‘The Necessity of Gardening’, Dirk Sijmons, whose brief was the Green Heart, argued passionately for a swift solution to the growing problem of water management in the Randstad. By now he has researched this issue so thoroughly and devised such attractive and thoroughly well-argued solutions that the government has only one option: immediately appoint Sijmons as head of water management and physical development in the Green Heart and adopt in full the recommendations of his proposal in the new government memorandum. Let’s not shirk the issue any longer, but implement what Sijmons has been advocating for years. To my knowledge there are no convincing alternatives, never mind attractive ones. So what are we waiting for?

Snozzi proposal

Snozzi presented his project first. In his proposal he deploys one architectural element to give further development an impetus. A circle, traced with mathematical precision, runs through the open area of the Green Heart and skirts the periphery of the large cities of the Randstad, passing east of Utrecht to complete the perfect shape. The ‘structure’ consists of a public transportation route, raised thirty metres above ground level, with monumental high-rise development at strategic points. Development is halted inside the circle; development outside is channelled over time towards the centres of the large cities. Space for the development of new towns is reserved at less densely built-up locations.

Snozzi’s proposal is alluring and absurd in equal measure. Construction of such a circle would instantly equip the Delta Metropolis with an enduring logo, and thus the identity of the Delta Metropolis would no longer be a concern. Great if this were possible, but of course it isn’t. The scheme totally ignores existing developments, cuts through administrative divisions with abandon, and fails to acknowledge development already under way. In short, it is not a proposal to structure future development but an architectural design elevated to a scale of planning possible only in centralist-run countries verging on the totalitarian. The requisite perfection of Snozzi’s circle would ultimately lose out to the inevitable but everyday reality of adaptation to local conditions. Architectural design – at least the classic, formal variety practised by Snozzi – makes little sense at the scale of the Delta Metropolis.

If Snozzi’s contribution serves any purpose, it is as a firm basis for discussing the influence (or lack of it) of architecture at the scale of the metropolis and the huge gulf that exists between the ideal plan and stubborn reality.

The four schemes are a response to questions put last September by Donald van Dansik of One Architecture, leader of the Delta Metropolis Design Workshop. The key question was whether, and if so how, the Delta Metropolis can be defined as a single entity. Does the area called the Delta Metropolis have an identity? Is it really a metropolis? If not, then what is it? Should it become a metropolis? If so, what needs to be done? Three teams specially formed for the Delta Metropolis Design Workshop were headed by Floris Alkemade (OMA), Dirk Sijmons (H+N+S) and Teun Koolhaas (TKA). The assignment for the teams was to consider the Delta Metropolis as a whole and test their design vision on a sub-area (OMA: Western Flank, H+N+S: the Green Heart, TKA: Northern Flank). A fourth team elaborated an earlier proposal from Luigi Snozzi.

Somewhat in the background, a completely different question was at issue, namely: to what extent is it worthwhile or productive to involve designers at an early stage of large-scale planning processes? Or put another way: Just how convincing is the core recommendation of ‘Shaping the Netherlands,’ the government memorandum on architecture?

Furthermore, the scale of the Delta Metropolis, a key government project, means it will have a significant bearing on the forthcoming ‘Memorandum on Space’ (formerly known as the Fifth Memorandum on Spatial Planning). All this was reason enough to look forward with keen interest to the workshop results. Though this may be simply an initial phase of investigation, every designer knows that the first lines committed to paper have a big impact on the final outcome.