The legendary exhibition Archigram experimental architecture 1961-1974 first went on show in Vienna in 1994. After travelling half the world, the exhibition has now arrived in Rotterdam. Models, installations, panels covered in drawings – all projects by the English Archigram group exudes the popular culture so typical of the 1960s.

Archigram started out as the name of a stencilled magazine whose first issue – which sold 300 issues – appeared in 1961. The name Archigram, analogous to words like telegram and aerogram, was an implicit reference to the transitory nature of the mag. Compiled by David Green and Peter Cook, it included projects by Michael Webb and a poem by Green. With Archigram, Cook and Green wanted to create a podium to publicise their own work and that of other young architects. Work not published in professional journals because, according to Cook and Green, it fell outside the modernistic canon. Archigram 2 appeared a year later. In 1963 the informal collaborative group of Green, Cook and Webb expanded to include Warren Chalk, Dennis Crompton and Ron Herron. Together they worked on an unrealised exhibition 'Living City': 'our belief in the city as a unique organism underlies the whole project'. The appearance of Archigram 4 in 1964, which featured 'Living City', signalled a breakthrough. An enthusiastic architecture critic, Reyner Banham, introduced the group to a wider audience. To him Archigram offered an alternative to the then prevailing views. They claimed that architecture was more than just building, that the scale of the city needed to be taken into account in design, that the city is more than a series of buildings, and that living should be considered as a logical continuation of human emancipation.

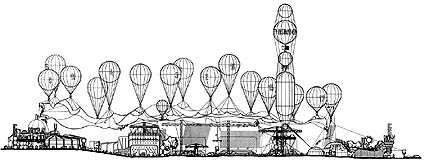

Instant City 1969-70 Ron Herron en Peter Cook

Employed in offices during the day, Green, Cook, Webb, Crompton, Herron and Chalk spent their evening hours working in different formations on designs of various scales. When in 1969 the Archigram team (now composed of Cook, Crompton, Green, Herron, Colin Fournier, Ken Allisson and Tony Rickaby) won a limited competition for a leisure centre in Monte Carlo, the core members decided to set up an independent practice. Five years later the practice was disbanded. In those five years Archigram succeeded in realising only a few small projects, among them the 'Instant Malaysia' exhibition design in the Commonwealth Institute in London (1973: Crompton, Herron), a children's playground in Milton Keynes (1973: Crompton, Herron), and a swimming pool for Rod Stewart at his house in Ascot (1973: Crompton, Herron with Diana Jowsey).

The importance of Archigram for architecture in the 1960s was that, similar to what was happening in other spheres of (cultural) life, it challenged the established order and sought a language to express a new order. Cook expressed it in 1967 thus: 'We are often asked about the Pop imagery. We are not really concerned about its connection or lack of connection with the movement in painting, graphics. There must be a connection at a dynamic or historical level between us and others.'

Faculty of Medicine, Aachen University

The world in which Archigram situated its projects was futuristic and apocalyptic. Explicable given the fact that the Cold War raged and the space race was in full swing. The buildings designed by Archigram are high-tech in appearance. The same visual language can be found in realised works like the medical faculty of the University of Aachen (1968-1986: Weber, Brandt & Partners) and the Centre Pompidou (1971-1977: Renzo Piano & Richard Rogers). 'The pre-packaged frozen lunch is more important than Palladio,' claimed Cook.

On the perception of Archigram's designs and ideas, Cook wrote in 1967: 'By bashing away at the architectural public in Archigram, but always being as concerned with the object as the idea, we became known by about 1964 as 'that lot'. Many young architects in London didn't agree with us. They are often embarrassed by the fruitiness of the objects as much as by the undermining of the continuing story of architects' architecture which is implied.' Critic Kenneth Frampton was also unimpressed by the work of Archigram. Partially citing Berthold Lubetkin, Frampton commented on the well-known Archigram project Plug-In City in his Modern architecture, a critical history thus: 'If anything was destined to reduce architecture to the level of the activities of certain species of insects and mammals [ ] it was surely these residential cells projected by Archigram.'

It is fantastic that almost all the work by Archigram can be seen together in Rotterdam in an exhibition designed by former Archigram member Crompton. It is regrettable that the exhibition is unaccompanied by explanatory texts. The visitor learns nothing about the ideas of Archigram, about the various projects, about the collaborative aspect of the group, the significance of Archigram, and so on. The publication Concerning Archigram, an abridged and adapted version of the official but out-of-print exhibition catalogue A Guide to Archigram 1961-1974, offers some pointers. Archigram compiled the exhibition and both catalogues, and they thus lack independent and critical reflection. Archigram are doing everything within their power to prolong their mythical status as avant-garde heroes for as long as possible, and they're doing it in style.