You, the ‘ordinary’ individual! Now log onto the municipality’s digital plot-shop, pick yourself a piece of land from and realize the house of your dreams. Welcome to 21st century city generation in Almere, the ‘adolescent’ new town of the Netherlands. Urban developers, large-scale construction firms and housing corporations are pushed off the stage and finally now you are given the chance to become the producer of your city. Your local government wants you to be proactive, creative and engaged!

Homeruskwartier, Almere

Talking about less formal urbanism, participation and customization let us now travel from Almere to Istanbul. Once the customized heaven of informality, the city still carries strong traces of self-made garden towns [gecekondu]. This self-service city of officially 14.000.000 inhabitants is generated in the absence of a visionary and powerful state and uncontrollable market economy. Not surprisingly, the city did not produce a single globally renowned architect or planner in the last century. It is not a question of talent. Architects, rather, were disconnected from the means of urban space production. They ignored a people-driven market and the market ignored them. As a result strong-willed individuals, poor or rich, have become the active participants and producers of Istanbuls communities. This explains very well Istanbuls disappointed elite modernists who could not participate in the construction of their city. Things could have been much different if the gap had been smaller between the energy of the ordinary people and architects.

However, participation-phobia of architects seems to be universal and rather timeless. Do participatory processes per se really diminish the influence of the architect and result in middle-of-the-road architecture? Will democratization of space production result in banal environments? We mentioned sour memories of architects from 60s and 70s. To my opinion today architects need to invest in finding out inventive interfaces enabling them to relate to users. This way results can still be product of a specialist but much more representative of given complexities. Elia Zenghelis, current research board member of Berlage Institute, in his speech during the Rotterdam Architectural Biennial 2007 Power in Kunsthal was rather bold about this issue: Architecture by nature is top down and participation is a Trojan Horse. Nobody can reject it and it causes damage after all!

One thing to consider before calling participation the Trojan Horse is the already questionable position of the architect in the context of the ever-influential market economy. As Dennis Kaspori in A Communism of Ideas [2003, Archis] wrote: The role of the architect in the building process would seem to have been reduced to that of a visagiste. The complete absence of any architect in the recent parliamentary enquiry into fraud in the construction industry should probably not be seen as evidence of their irrefutable morality, but as proof that they play hardly any part in Dutch spatial planning. The architect is happily doodling away indoors while the big boys are outside building huts.

Choices are clear: stylist and working for big boys or activist and working with people.

After 100 years of regulated and top-down organized housing practice, Dutch citizens are now called to take charge of this practice and transform themselves into developers. Settlements built by conscious and responsible users are envisioned as a strategy for generating a more dynamic city. Evolutionary Istanbul neighborhoods like Gulensu or Karanfilkoy — first informally built by their inhabitants are living example of this. In these places users needs and their adaptations in time can be expressed and observed through physical space. Obviously Almeres inhabitants will have their own urgencies and dynamics that will differ from those of Istanbul. Diversity is high on this list, with a 27% foreign-born population that is second only to Rotterdam, an increasing rate of single mothers and the elderly. The challenge is about how free individuals will find a way to reflect the complexity of the society under existing rules and regulations structures.

How will Dutch architects position themselves now? As the welfare state slowly modifies and market forces take over, developer friends might choose to take the short cut. Just as it happened in Istanbul they may decide to ignore their cool architect friends one day.

Or architects may choose to take the role of an activist and seek out new ways of connecting with the society.

A way will be found in engaging people and releasing the complexity of the current society through self-organizing environments. This is where the innovation in architecture will take place in 21st century.

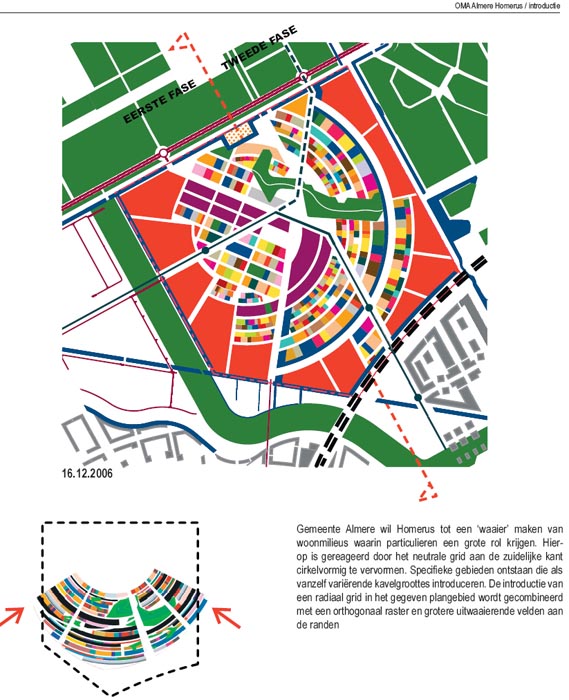

This is not just a bunch of housing projects attached to a new town but the largest housing production endeavor of the coming decades in the Netherlands. 60.000 new homes are envisioned to be built by 2030, one-third (20.000) of which is to be customized by their owners. Driven by the motto Ik bouw mijn huis in Almere/ I build my house in Almere, this city would be created not only for people but by them. This strategy is expected to deliver a more complex, unpredictable, and spontaneous city than the carefully engineered and controlled one of the present.

Does this mean the end of the standardized, normalized, and overregulated Dutch housing production machine? Could this mean the prospect of informality in a system of controlled formality? Obviously traditional actors and mechanisms producing the city need an entire adaptation. This change will take generations of evolving design processes.

It is important to interpret the ongoing developments in Almere as a natural consequence of a changing economy and a welfare state in transition. Production and consumption processes are changing, as do practices of governance. It was 1993 when Joseph Pine came out with his book Mass Customization. He was basically pointing out emerging systems of new customized production, such as in the car industry in competitive countries like Japan. For governance, it is no longer revolutionary to see cities as a collection of self-organizing complex systems where both bottom-up and top-down processes intermingle.

What still needs to be clarified is the position of the people and the designer in relation to these changing complex conditions. More collaborative approaches are natural as the information becomes accessible for bigger crowd, society gets more complex, life styles more diverse, individuals more conscious, critical and demanding than ever before. And open systems allow everyone to take part in complicated processes. [e.g. wikipedia, second life] Companies like Philips and Nike are among the ones who understand this trend, they create departments specializing in user centric design approach. One can go to http://nikeid.nike.com and start customizing the dream clothing and shoe with favorite colors, textures, materials. This will definitely have its reflection on the field of architecture. It on the other hand reminds architects bitter experiences of 60s and 70s, mainly colored by political influences of that day. However, this time dynamics are completely different. At that time people, advocate planners and leftist architects were asking their participation rights, today politicians, companies, planners are in need for active and responsible people for taking part in developments.