Rotterdam, 18xx. A man standing on the northern margin of the river Maas spots another person strolling along the southern bank. He cups his hands to his mouth and yells: Hey, how do I cross to the other side?. To which his southern neighbour responds: I dont know. I was born here. Although the Manzanares is approximately ten times narrower than the Maas in Rotterdam throughout its metropolitan stretch, it stood as a mixture of a mute onlooker and a feeble bastion throughout the eventful southern expansion of Madrid. A sort of a hurdle race in which the city, on and on, has jumped over self-generated, programmatic barriers as they reached a critical state. Until Madrid Río opened to the public.

The struggle with the Manzanares began as a consequence of the Castro Masterplan from 1848 and the subsequent demolition of the city walls the first barrier, which, together with the incipient Industrial Revolution, strewed the northern river bank with all sort of productive buildings. In order to grant their connectivity, a railway line between the actual Atocha and Príncipe Pío stations was built, casting a second physical barrier that was overcome after the 1963 regulations, which were to wipe out any industrial remains from the area. The massive housing sprawl that had ensued from these developments clustered in increasingly chaotic neighbourhoods as one heads south – contributed to the creation of the M-30, a circular motorway framing the consolidated metropolitan core, and running parallel to the river in its south-western sector. Just like a Gordian Knot is undone, this multiple-track, heavy traffic flow plus the A-4 motorway outlet was boldly undermined in 2004, in one of the most significant urban surgery operations the city has ever been through. Thus, the river appeared again as an original yet insignificant southern barrier but this time it actually depicted two radically different urban conditions: the peripheral instability characterized by an increase of the populations age, a massive increase of immigrants, high criminality rate and a lack of entrepreneur activity, and the consolidated almond1.

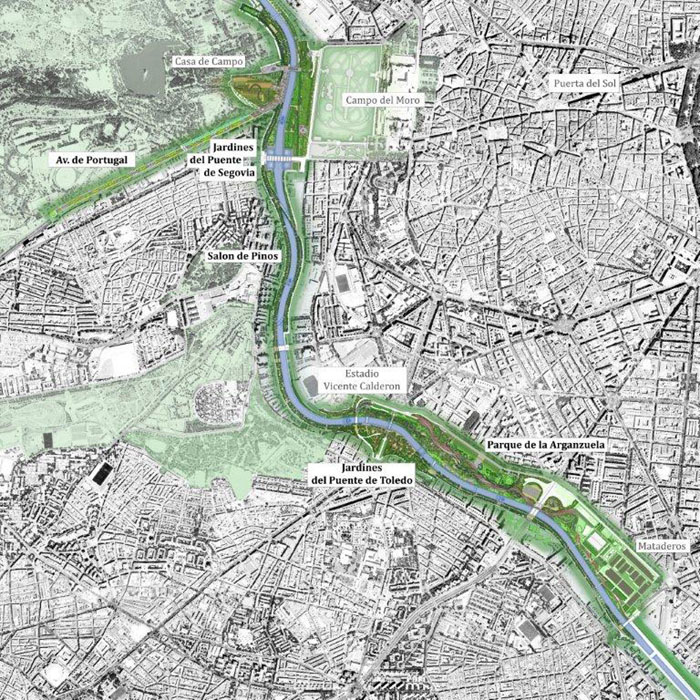

An international competition was held with the aim to regenerate the original riverbank, integrating the leftover wastelands originated by the M-30 burial. The winning entry carried out by Mrio Associated Architects2 and West8 seemed to envision the underlying dimension of the commission, and managed to answer accurately to an array of unasked questions providing a bunch of trustworthy incentives.

Within a socio-political context, Madrid Río could be described as a kinetic operation. Kinetic, for its approximately 120 hectares park works as a social condenser which agglutinates the habitual activities carried out on both margins, dissipating some of the former over-congestion from the southern bank and seamlessly linking this site to the city centre once and for all. And kinetic, because it bears no further potential through which the city may evolve into a more complex and richer organization. Therefore the projects foreseeable scope turns out to be extremely appropriate in a Spanish metropolitan context, for traditionally urban potentials have been seized with speculative purposes, thoroughly endangering the fate of our cities. This integral, bold operation is, in that sense, the best thing that could happen to Madrid.

Besides, its praiseworthy empathy has bestowed Madrid Río with perhaps the cornerstone of real urbanism, referred by José Miguel Iribas as the immaterial components that represent the cultural and social basis upon which the urban condition is founded3. Like Times Square or Picadilly Circus, and despite its short existence, Madrid Río is intensively used by citizens of all ages as if the river bank had always been as it currently is, while its astonishing social success silences its architectural features and details: nobody seems to care for the stripped, granite-clad batter walls or the Portuguese-like, lavishly tessellated flooring. Perhaps this is because these ornaments, plus an array of details belonging to the Iberian tectonic catalogue, are stored into the collective memory of the Spaniards, and therefore, somehow, empowering Iribass assumption. The pragmatic denial of the river, neglected as an active urban element, relegated to an objectual condition and furnished with all sort of sectorized attractors, evidences a clever understanding of Manzanaress fate. Doomed since the nineteenth century and mercilessly polluted nowadays, the river could have never turned into what the foreign contestants (Herzog & de Meuron, Perrault, Eisenman + Corner and SANAA) intended it to be. Not only because the brief did not demand it explicitly4, but also because a natural resource management plan is invisible and, therefore unappealing to investors and quite frankly, to a vast percentage of the Spanish population.

The 10 kilometre promenade features some interesting spots, such as the yet unaccomplished merging of the old slaughterhouse (currently turned into an important cultural venue) into the linear park, or the situational diversity of the brand-new Arganzuela Park, to mention some. These and more are accurately described in the architects memorandum, as well as in the wide range of ubiquitously published pictures. But its Kwinterian5 infrastructural idiosyncrasy is to my mind what makes the effort worth. To acknowledge its values properly, the project demands an active flâneur, wary of the rivers previous border conditions and global state. The most adequate way, however, might be experiencing its excited state turned on by the users.

Nowadays in Madrid one of the trendiest topics is highlighting the pharaohic scale of the project and the irrational sum of money involved in its completion. The fact that the city will be beset by substantial debts for many years cannot be denied. However, it is appalling to see how this debate is frequently instigated behind a veil of tacky snobbism by certain architects or planners that have been responsible for the worst peripheral developments in the citys contemporary history. These in sum might be as expensive as Madrid Río, which in turn has managed to sew an urban scar efficiently, reinforcing the social and cultural structures of the adjacent neighbourhoods and densifying a formerly stranded area, located less than one kilometre away from the Royal Palace. Of course, there are certain perverse questions that one may ask. Is there any unprofitable thermodynamic potential within a buried motorway? Could some of the expensive details such as the ones that garnish the tunnels ventilation ducts have been swapped for a better management of the river basin as the water still stinks? Could the congestion derived from Vicente Calderón, the 55000-seat stadium and home to Atlético de Madrid, have been managed throughout a better arrangement of the urban flows and infrastructures, and so avoid the demolition of the stadium? Are we still approaching the urban contingence only in terms of visual or academic analysis? These and more questions will remain unanswered forever. Nevertheless, they all point to one direction, which Federico Soriano depicted some years ago: The juries are the truly challenged contestants in any competition6. I totally agree with his statement not only because of the jury’s ability to decide on the cities becoming, but because of their indulgence when approving a competition brief. Sometimes, they are strictly focused on design and lack a dose of transversal approach.

As Lacaton & Vassals Léon Aucoc square in Bordeaux demonstrates, there are several strategies that bear more architectural properties than traditional means, which, sooner or later, will not be enough to satisfy our contemporary metropolitan demands.