While political leaders have managed to destroy the European social model in both word and deed in recent decades, a retrospective of Bakema’s vision of architecture and an open society is an ode to a direction that was not pursued further. In this vision, the Netherlands is modern and completely urbanized, and of course designed in a modernist manner down to the last detail. Acknowledging that recent decades have seen little progress towards an open society is, however, not the same as abandoning belief in progress. This article concludes with an ode to direct action on the street, a place where democratic changes usually start.

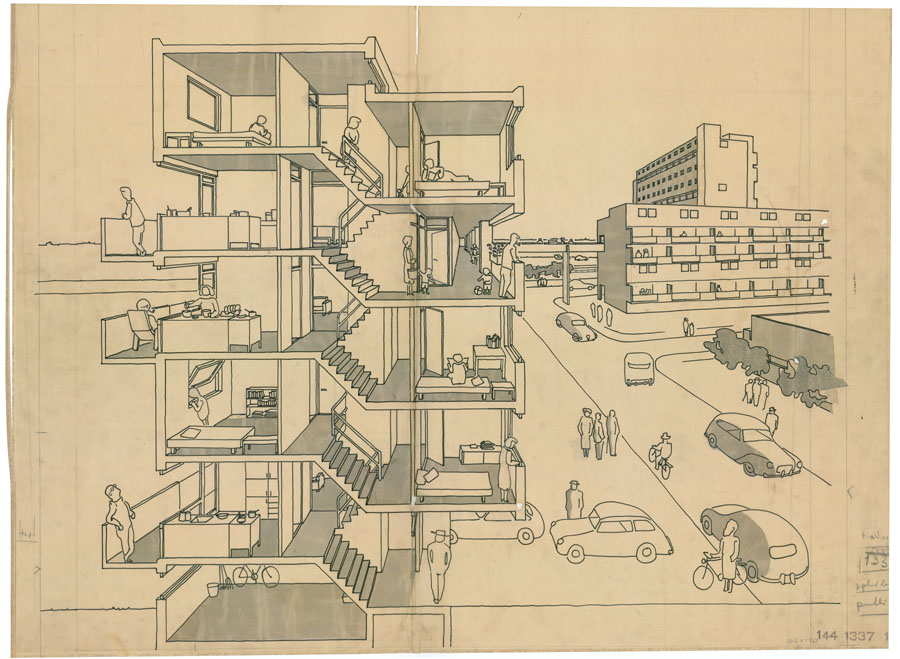

Page from the manuscript Van Stoel tot Stad, een verhaal over mensen en ruimte, Jaap Bakema, 1963, collection Het Nieuwe Instituut BAKE d276

In the early 1970s Jaap Bakema and architecture theorist Jürgen Joedicke published a retrospective entitled Architektur – Urbanismus, Architecture – Urbanism, Architecture – Urbanisme. The book contains descriptions of projects by the office of Van den Broek en Bakema. In the margins, Jaap Bakema, then in his early sixties, outlined once again his vision of architecture, urbanism and society.

Bakema starts the publication by announcing that a second (industrial) revolution is taking place, characterized by ‘automation, total urbanization, and democratization of the social decision-making processes’. [i] Here he reinterprets Reyner Banham’s concept of the Second Machine Age[ii] and places himself in a Marxist context in which students, not the proletariat, carry the torch of revolution. Bakema envisages a mechanized future in which greater industrial efficiency enhances the quality of life of citizens,[iii] and at the same time he expresses concerns about the environment,[iv] and about the 19th-century model of unbridled exploitation and expansion that paved the way for the Industrial Revolution.

Bakema’s text is written in dogmatic style. He presents himself as both an activist and a leader who wants only the best for the people. His ideas for the ‘open society’ rarely move beyond generalizations, and he has a tendency to reduce complex political, social and moral questions to design problems. The idea that modern architecture is on the one hand an academic project and on the other an idealistic and liberal one that expresses an ‘all-embracing hope’ for humanity was widely accepted and supported at the time.[v]

The large-scale architectural urbanism of Van den Broek en Bakema reaches its apotheosis in the unrealized project for Pampus, Amsterdam (1965). Proposed as a vision of the total urbanization of the Netherlands, the Pampus project consists of core-wall buildings, or megastructures, attached to an infrastructural ‘spine’ that meanders through the landscape, alternating with smaller residential units and blocks of flats. It is natural for an open, democratic society to be formally translated into modernist megastructures[vi], or vice versa, that Bakema’s architecture of carefully designed ‘thresholds’ or ‘transitional elements’ will automatically lead to a democratic, open and egalitarian society. Bakema’s romantic vision can only be understood as the result of a modernist belief in progress, against the background of the Cold War and in the context of the welfare state. The post-war reconstruction period is characterized by optimism inspired by strong economic growth and a reduction in income inequality. These trends were the result of the successive economic shocks after the stock exchange crash and World War II, followed by Keynesian economic policies, but they were inaccurately viewed in the 1950s as the natural direction of capitalism in its late phase of development. In 1955 the economist Simon Kuznets even contended that income inequality follows a bell curve; inequality grows during the first phase of industrial development, but this is later corrected as a higher percentage of the population share in the increasing affluence. It is notable that Kuznets does not think that social events or revolutions are necessary — as Marx in particular had thought — but that this fairer distribution of wealth will come about through the internal working of the market, i.e. without external intervention.[vii]

[i] Jürgen Joedicke, Architectengemeenschap Van den Broek en Bakema, Architektur – Urbanismus, Architecture- Urbanism, Architecture – Urbanisme, Stuttgart 1976, p. 6:

“Now, in 1975, the second revolution of our century is in full swing; it is characterized, among other things, by:

automation,

total urbanization,

democratization of the social decision-making processes.

The first revolution, which took place between 1910 and 1920, was essentially determined by:

mechanization,

new architecture,

mass society.”

[ii] Reyner Banham, Theory and Design in the First Machine Age, London 1967 (orig. 1960), p. 10: “A housewife alone, often disposes of more horse-power today than an industrial worker did at the beginning of the century. This is the sense in which we live in a Machine Age. We have lived in an Industrial Age for nearly a century and a half now, and may well be entering a Second Industrial Age with the current revolution in control mechanisms. But we have already entered the Second Machine Age, the age of domestic electronics and synthetic chemistry, and can look back at the First, the age of power from the mains and the reduction of machines to human scale, as a period of the past.”

[iii] Jürgen Joedicke, Architectengemeenschap Van den Broek en Bakema, Architektur – Urbanismus, Architecture- Urbanism, Architecture – Urbanisme, Stuttgart 1976, p. 72 “It is true that in the future there will no longer be enough work for everybody, or if working hours are shortened, then in his spare time the inhabitant should be able to expand his house…” Bakema refers to an article by him in the periodical de 8 en Opbouw, no. 9 1942, in which he explains that the structural unemployment caused by mechanisation should be solved by changing the ownership relationships of the means of production. This is also a position adopted by the first CIAM congress: “The idea of ‘economic efficiency’ does not imply production furnishing maximum commercial profit, but production demanding a minimum working effort.” La Sarraz Declaration, 1928 English translation, Ulrich Conrads, Programmes and Manifestos on 20th-Century Architecture, Cambridge (Mass.) 1970, p. 109.

[iv] Jürgen Joedicke, Architectengemeenschap Van den Broek en Bakema, Architektur – Urbanismus, Architecture- Urbanism, Architecture – Urbanisme, Stuttgart 1976, p.28 and p. 47

[v] Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter, Collage City, Cambridge (Mass.), London 1983 (orig. 1978), p.3

“By one interpretation, modern architecture is a hard-headed and hard-nosed undertaking. There is a problem, a specific problem, and there is an obligation, an obligation to science, to solve it in all its particularity; and so while without bias and embarrassment we proceed to scrutinize the facts, then as we accept them, we simultaneously allow these hard empirical facts to dictate the solution. But, if such is one important and academically enshrined thesis, then, alongside it, there is to be recognized a no less respectable one; the proposition that modern architecture is the instrument of philanthropy, liberalism, the ‘larger hope’ and the ‘greater good’.

In other words, and right at the beginning, one is confronted with the simultaneous profession of two standards of value whose compatibility is not evident. On the one hand, there is an expression of allegiance to the criteria of what – though disguised as science – is, after all, simply management; on the other, a devotion to the ideals of what was a few years ago often spoken of as the counter culture – life, people, community and all the rest; and that this curious dualism causes so little surprise can only be attributed to a determination not to observe the obvious.” The big difference between Rowe and Bakema is that Rowe acknowledges the inherent contradictions of the modern project.

[vi] For an interesting criticism of the proposals by Bakema for Amsterdam and Tel Aviv, see Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture – a Critical History, London 1992 (orig. 1980), p.274.

[vii]Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge (Mass.), London 2014, p.14 Piketty explores in depth the difference between the optimism expressed publically by Kuznets and the reservations he voiced in his academic work.

Pampus Amsterdam, 1964, collection Het Nieuwe Instituut, BROX 1411t5-2, Van den Broek en Bakema Architecten

Against this background, Bakema’s faith in the uneasy marriage between social democracy and capitalism is understandable, a faith so strong that Architektur-Urbanismus pays almost no attention to the fact that the basis of architecture is not only societal but also economic. The Italian architecture theorists Manfredo Tafuri and Francesco Dal Co had already pointed to this blind spot:

“The directional systems and new proposals, even in their most thorough variants such as the projects of Bakema for Tel Aviv-Jaffa and for the over-water expansion of Amsterdam, remain on paper. There is a reason for this bankruptcy. […] It fails to take into account the necessity for a direct linkage between hypotheses of new modes of production and institutional reforms. In other words, despite themselves the utopian-futuristic architects of the last decade have simply gone along with a more-than-traditional division of labor; their vaunted individuality is a last ditch where they dig in their heels to safeguard an autonomy that is, at best, unproductive.”[i]

According to this interpretation, radical social change can only be achieved by questioning the capitalist foundations of society and revising current power and ownership relationships. The difference between Bakema and Tafuri and Dal Co is that the former, despite the use of inflammatory rhetoric, largely advocated gradual change within the system, while Tafuri and Dal Co regretted as early as the 1970s that the social unrest of the preceding decade had not led to fundamental change in traditional labour and power relationships. They too could not envisage that the call for more individual freedom, participation and equal rights would lead to the reactionary counter-revolution of neo-liberalism and the almost complete dismantling of the welfare state.[ii] The economic shocks of the oil crisis of the 1970s heralded, as we now know, the start of the Hayekian transformation of the economy, in which the fiscal crisis of liberal democracies was ‘solved’ by higher national debts, globalization, and deregulation of financial markets, combined with extensive privatization of state property and services.[iii] According to sociologist Wolfgang Streeck, this transformation marks a power shift from democracy to an international financial and multinational elite that is not subject to democratic accountability.[iv] Governments are increasingly concerned about maintaining ‘confidence in the market’, even if this leads to the further marginalization of the weaker members of society, the destruction of social services and the weakening of democratic legitimacy. The conflict between democracy and capitalism intensified with the crisis of 2008, the bail-out of the banks and the austerity measures, but this process of erosion had been occurring for decades.

Change

If we look back at the model of the open society advocated by Bakema, a model based on greater democratic participation, automated production and local and total urbanization, then we must acknowledge that progress in all three areas has been an utter failure.

Democratic participation and belief in politics has declined, automation is applied to minimize wages around the world — leading to exploitation and growing income inequality — and urbanization in the Netherlands is left to market parties, privatized housing associations and property speculators, with all its dramatic consequences. Growing insight into climate change has increased concerns about the environment. In considering these macro-economic tendencies and recent political developments, we can ask what individuals can do to stem the depressing tide. It is striking that the only time Bakema uses the term ‘open society in the book Architektur-Urbanismus is in his appeal for more democracy, and he links it directly to the implications for architects: “Society must become more open, more democratic. What exactly does this mean for our profession?”[v]

[i] Manfredo Tafuri, Francesco Dal Co, Modern Architecture, New York 1979 (original 1976), p. 390.

[ii] In an interview with the Wall Street Journal in 2012, the chairman of the European Central Bank stated: “The European social model has already gone when we see the youth unemployment rates prevailing in some countries. These [structural] reforms are necessary to increase employment, especially youth employment, and therefore expenditure and consumption.”

http://blogs.wsj.com/eurocrisis/2012/02/23/qa-ecb-president-mario-draghi/, website visited on 26 October 2014.

[iii] Wolfgang Streeck, Buying Time – The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, London, Brooklyn 2014, p. 72-73, in the chapter ‘From Tax State to Debt State’, this transformation is expressed as follows:

“If the fiscal crisis of the state […] is situated on the revenue rather than the expenditure side – then we are struck by two trends of the recent decades that no one foresaw in their actual significance. The first is the transformation of the tax state into a debt state – that is, a state which covers a large, possibly rising, part of its expenditure through borrowing rather than taxation, thereby accumulating a debt mountain that it has to finance with an ever greater share of its revenue. […] But it should be noted in advance that the formation of the debt state was impeded by a countervailing force which, in the neoliberal reform movement of the 1990s and 2000s, sought to consolidate government finances by privatizing services that had accrued to the state in the course of the twentieth century. This was the other historical development that the crisis theories of the 1970s had not yet been able to foresee.”

[iv] Ibid. from p. 79 on he argues that a bigger gap has emerged between the interests of the Staatsvolk, a term for the citizens of independent nations, and the Marktvolk, an internationally operating financial elite. See also: Joseph E. Stiglitz, Freefall – America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy, New York 2010. This book examines the 2008 crisis in great detail. Stiglitz is a strong advocate of more regulation and Keynesian economic policy, and argues that the neo-liberal economic model has in fact little to do with the working of the free market, but is based on a far-reaching and unhealthy intertwining of politics and marketplace.

[v] Jürgen Joedicke, Architectengemeenschap Van den Broek en Bakema, Architektur – Urbanismus, Architecture- Urbanism, Architecture – Urbanisme, Stuttgart 1976, p. 101

Dwellings Lekkumerend, Leeuwarden, 1962, collection Het Nieuwe Instituut, BROX_1337t339-1, Van den Broek en Bakema Architecten

The answer, according to Bakema, is both architectural and administrative. He appeals for the humanization of architecture by emphasizing the human scale and expressing social relations, and he stresses the need to implement sound urban-design policy through zoning plans. Here Bakema is searching for a balance between individual and collective needs and thinks that participation and responsibility of citizens should be increased to achieve that.

Neo-liberalism has successfully co-opted the concept of individual freedom to weaken larger connections in society and to call for less government involvement.[i] This increase in individualism, combined with the constant emphasis on consumption, has led to the fragmentation of society, as reflected in the declining participation in societies, trade unions and political parties. The idea that the individual is on his own — in spite of new means of communication — is a major obstacle to change. Bill McKibben, a prominent climate activist and journalist, realized that writing books about climate change in order to raise awareness among people is not enough:

“It took me a long time to realize that the scientists had won the argument but were going to lose the fight, because it isn’t about data and science, it’s about power. The most powerful industry is fossil fuel, because it is the richest. At a certain point, it became clear that our only hope of matching that money was with the currencies of movement: passion, spirit, creativity—and warm bodies.”[ii]

So on 21 September my wife and I took part in the People’s Climate March in New York, joining a multitude of singing and dancing people from America and all over the world. Television usually creates the impression that society is completely polarized, while here we had farmers from Nebraska, Native Americans, Hare Krishnas, vegans and victims of Hurricane Sandy walking side by side. We were no longer alone, isolated behind our computers, but part of one big, peaceful movement. People did of course realize that demonstrating and sending one signal is not enough, to view the climate problem separately from the prevailing social and economic inequality. Political and social changes need to be fought for, along the paths of direct action, the ballot box, and everything in between. Even so, the sense of collectivity was a transforming experience. In any case, a start has been made.

For architects I think that the ambiguous answer given by Bakema still holds true. For us it is indeed a political and physical problem, or in the words of Tafuri, a matter of redistribution of means of production and institutional reform. Architects are well positioned to acquire knowledge, organize themselves and formulate and visualize an alternative vision, and to communicate this with a wider audience. We cannot wait to see if the Dutch political class ever again supports a progressive vision of public housing, planning and urbanism without the application of some pressure, or without people being aware of alternatives to the terror of ‘the market’. I do not know how many bodies are needed to extract ‘democracy’ from the power clutches of business and Wall Street, how loud our voices must be to end political stalemates, but what I do know is that the open society is more a verb than a fact.

[i] David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism, New York 2011 (orig. 2005), p. 5. “The founding figures of neoliberal thought took political ideas of human dignity and individual freedom as fundamental, as ‘the central values of civilization’. In so doing they chose wisely, for these are indeed compelling and seductive ideals. These values, they held, were threatened not only by fascism, dictatorships, and communism, but by all forms of state intervention that substituted collective judgements for those of individuals free to choose.”

[ii] Bill Mc Kibben, Interview by Jay Caspian Kang, The New Yorker, 20 September 2014, http://www.newyorker.com/tech/elements/peoples-climate-march-interview-bill-mckibben, (viewed 2 November 2014).

People’s Climate March. Photo Stephen Melkisethian