Thursday starts the conference Constructing the Commons at the Faculty of Architecture and Built Environment TU Delft. Constructing the Commons investigates the commons from an architectural point of view. Yoshiharu Tsukamoto of Atelier Bow-Wow is one of the key note speakers.

Copenhagen

Commonality is not an everyday term. In Japanese, it holds the meanings of the words kyōyūsei (共有性: the quality of being jointly owned or shared) and kyōdōsei (共同性: the quality of working together or of being united). We are not familiar with its use in other disciplines, but the term has rarely been used in architecture. Among architects, we have only found evidence that Louis Kahn used the term. According to Kahn, the reason we are moved by ancient constructions is because we are connected to one another by things deep within us that transcend time and place, and these things are commonalities. Notions similar to this can be recognized in what Jørn Utzon describes in his essay ‘The Innermost Being of Architecture’ (1) — the idea that the present is linked to the past by the intelligence of human beings embedded in architecture — and in what Christopher Alexander describes in his essay ‘The Timeless Way of Building.’(2) These are encouraging expressions that suggest that it is possible for those in the present to link with those who erected the early constructions that seemed to have risen out of the earth.

These ideas evoke a return toward an origin. However, one must be careful in returning to origins, because doing so tends to lead to a search for prototypes in a reductive manner through the disregard of time- and place-specific transformations. Our discussion on commonalities in architecture continues this line of thought. We, too, are focusing on the emergence of intelligence in architecture, but we diverge from it in how we understand human behaviors and architectural types as things that are generated ‘by chance’ through the combination of various conditions. We are doing so because this viewpoint allows us to re-grasp the transformations that behaviors and types undergo over time as things that help us perceive changes in their boundary conditions. We cannot avoid dealing with boundary conditions if we are to create things to be shared, or commonalities. We are employing this genealogical approach in an attempt to bring the commonalities in architecture into the context of design.

What is now needed for assessing this are means for perceiving commonalities. Situations in which commonalities have been given form or have become perceptible include the condition when similar but slightly different buildings recur in a particular locale or along a street. Despite different owners, each building participates in shaping the town landscape or urban space with their roofs and façades, forming a collective whole that transcends private ownership. Features observed in buildings regardless of their individual differences are typologies. However, this understanding of typology is through the vantage point of the researcher. With regard to commonalities, we understand that the people living in a place share a common architecture. In other words, the fact that typologies exist signifies that people understand what type of architecture is appropriate for the particular region or community in which they live. Such people have confidence in themselves, and pride in their communities.

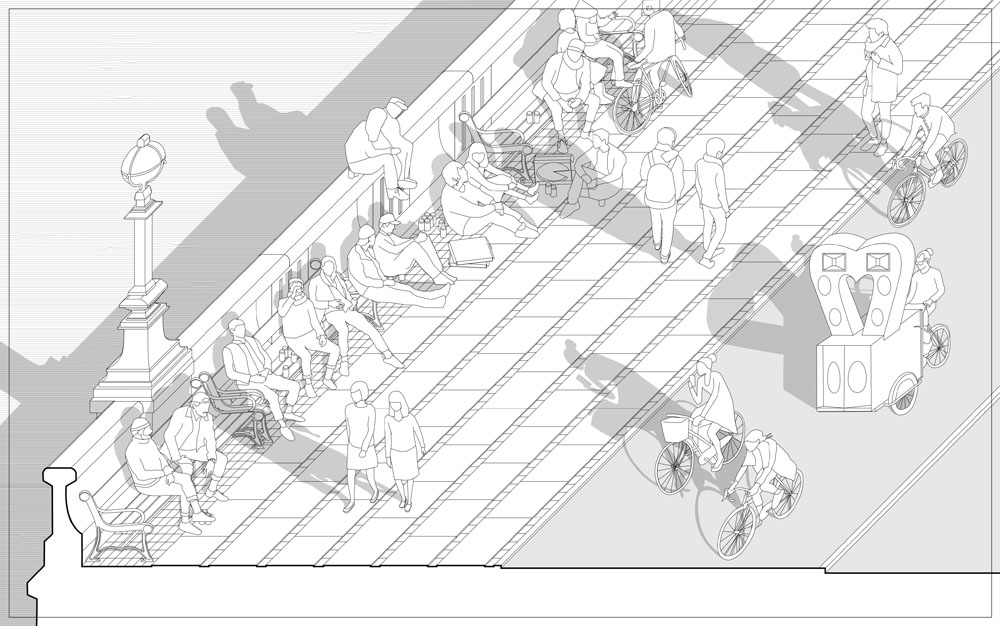

Another situation where people are behaving freely is in the urban plaza. However, the people in this space will rarely behave in entirely unrelated ways; rather, their behaviors converge upon a certain set of behaviors. Behaviors can be seen as types also, and they can be repeated in a particular place by transcending the differences of their subjects. This enables strangers to have common ownership over the same time and place while acknowledging each other’s differences without interference. A person can acquire these behaviors through repetition. They can be learned. These behaviors belong to each person, but simultaneously belong to the place, and no one person can have exclusive possession of them. Conversely, it is not easy to prevent others from behaving in the same way. The behaviors are both an asset to the individuals who acquire them and a shared asset of all the people. The behaviors of those who are acquainted with how to behave are refined, and there is something gentle and comforting about them. In fact, this is why they are permitted to have ownership over public spaces, if only temporarily. This privilege adds breadth to people’s lives. This makes people become tolerant toward others as well.

Therefore, a shared trait between architectural typologies and human behaviors is that they are perpetuated in particular regions and neighborhoods while transcending the differences of their subjects. What makes this possible is the existence of types. Considered over the long term, types change incrementally while retaining their primary attributes. Types always accompany forms and cannot exist alone as physical constructs. Types form where balances are found between various factors, such as climatic, material, lifestyle, institutional, and economic. Hence, by looking at types, we can appreciate how there are certain mutual linkages taking hold between things in which an infinite variety of combinations are possible.

Copenhagen

Types subtly change over the years because new balances are established when any one of the numerous factors that constitute the mutual linkages change in quantity, are lost, or have new factors integrated into them. For instance, the balance maintained between a craft artist’s ceramic artwork and nature is not the same as the balance maintained between mass-produced pottery and nature. In the former, the value of the artwork lies in how its form is found through a dialogue with nature (clay); in the latter case, the value of the product lies in how it is made to have no imperfections by suppressing any individual inconsistencies in the clay that is transferred to a mass production scale. If the relationship of the individual pieces to nature were to be mobilized on a mass scale for the purpose of manufacturing products, this would mean that the degree of interaction with the elements of nature would become imperceptible among the various factors that constitute the mutual linkages associated with pottery making. The qualities of regional specificity would also diminish with it. Genealogical studies reveal changes in mutual linkages by introducing a time-scale into the transformation of type. A genealogical examination enables the mutual linkages to be re-read as things that are dynamic, rather than static. Both architectural typologies and human behaviors are produced over and over again within mutual linkages. In this sense, they serve as indicators of the conditions of a particular place.

Architectural typologies and human behaviors can be seen as materialized forms of commonalities extending from our earlier studies of behaviorology.(3) Our focus with behaviorology has been on the behaviors of natural elements (light, wind, heat, humidity, water, among others), people, and architecture (typologies) that are repeated with their own particular rhythm while transcending the differences of their subjects. We have been observing how intelligence emerges in the architecture when it integrates these different behaviors in one physical entity. Our claims in behaviorology have been grounded in the practical consideration that we gave to independent problems by utilizing the insights that we gained from our observation of these behaviors. The observation of behaviors demands that we ascertain what things can and cannot be altered among the factors that shape the behaviors. For instance, we cannot alter the fact that water flows downward in accordance with gravity, but we can alter how the water flows by modifying the surface on which it travels. It is as if the attributes unable to be altered preserve their invariability by making use of those that can be altered; while the things that can be altered change by making use of the attributes that cannot be altered. The concept of commonalities is introduced in order to extract such mutual linkages or relationships that exist latently among typologies and behaviors and to make them a common resource accessed by all.

The thread of reasoning behind commonalities that leads from typologies and behaviors to mutual linkages is important because it resists against the fragmentation of life, particularly in today’s urban areas. However, this resistance does not fit into the conventional scheme in which there are individuals who are resisting against a state or social system oppressing them. Rather, it can be thought of as a resistance to the thought that the individual inherently exists. In actuality, the notion of the individual has been created interdependently with the social systems, such as the state, like two sides of the same coin. What has been carelessly swept away in the process is the intermediate realm of the common. There should be rich commonalities, which, like behaviors, can be acquired by individuals while also belonging to particular places. If we look at behaviors, the individual and the common appear to merge with one another making it difficult to distinguish between them. However, this involves too much diversity to be handled within a public system, which is why it is assumed that people are individuals, or empty bodies.

Twentieth-century architecture played a significant role in reinforcing this transformation. Modernist collective housing and detached housing developments represent examples of architecture’s role. Collective housing, intended to address postwar housing shortages, was premised on delivering dwellings on a mass scale, so the family unit was superimposed onto living units, producing uniform spaces through fair, equal repetition. Within this uniformity, collective housing projects were zoned into three distinct areas: space for the family (individual realm), spaces used collectively by the residents (common realm), and spaces freely accessed by outsiders (public realm). These distinct realms for the individual, common, and public could be calculated into floor areas. The individual was typically limited to families and singles. However, residents were assumed to be empty, skill-less bodies. The projects provided common areas for connecting individuals to give meaning to the fact that they lived together. Yet, these common areas were typically nothing more than calculated floor areas set aside, merely representative of the common. Nobody knew how to use the common spaces, so they were overrun by rules written to prevent inconveniences to others — such as ‘No Ball Games Allowed,’ ‘No Noisy Activities Allowed,’ or ‘No Open Flames,’ — ultimately becoming common nuisances that required maintenance costs but were unable to be used for anything.

Other realms that are accessible to all, such as the plazas in front of public facilities and the open areas that are created at the base of high-rise buildings in exchange for eased floor area ratios, also expect residents to simply be empty bodies. Open spaces are necessary at the base of high-rise buildings for emergency evacuations of large numbers of people in a safe manner. The dimensions of such spaces should obviously correspond to the sum of quantifiable individuals. However, so-called “one-sided” public spaces with no consideration for the space of the street or their neighborhood are increasingly everywhere.

The boundary of the individual is assumed to exist as a matter of fact when decisions are made based on these vaguely defined common spaces and one-sided public spaces. This leads to the possibility that individuals might be split apart more than connecting them. As more collective housing and open spaces designed in this manner continue to be constructed, people become accustomed to the relationship between the individual and public according to the notion that the sum total of measurable individuals is equal to the whole (public).

Architectural design that integrates commonality must challenge the notion of the individual as an ‘empty body.’ This undertaking is sure to reflect concerns about the fragmentation of modern life, misunderstandings of the mutual linkages between things that really should be giving direction to lives, and how things that used to be part of people’s daily life — realm of commonalities — have been transplanted into the industrial realm. It is more effective to tie realms to everyday life, such as dwellings that are designed to be repeated, streets shaped by the repetition of such dwellings, and open spaces in which people can gather. These are the realms that will produce the rich behaviors that fall outside conventional categories and that cannot currently be observed in the spaces systematized within twentieth-century building types.