It was a perfect June evening in Aspen, a former silver mining town 8,000 feet up in the Rockies. As the sun began to dip behind the snow-capped mountains on this first day of the 1970 International Design Conference at Aspen (IDCA), a group gathered for a cocktail party. The men were dressed in plaid jackets and ties and their hair, if they still had any, was close-cropped and gray. Their wives wore cocktail dresses, large sunglasses and pearls, and their hair, curled and set, barely moved in the breeze that ruffled the nearby aspen trees.

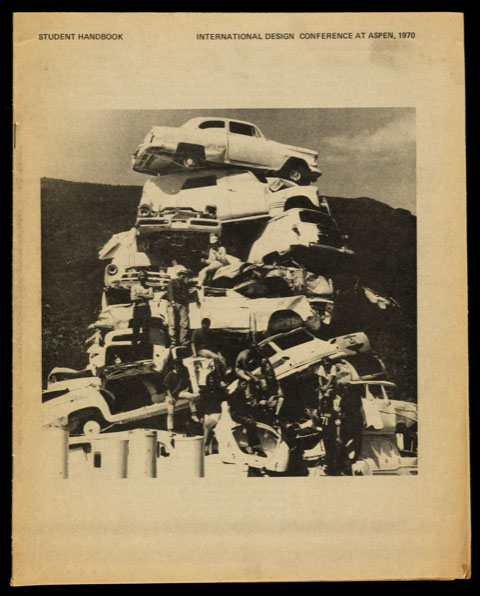

cover Students handbook International Design Conference at Aspen, 1970

Drinks were set out on the terrace of one of the modernist houses in the Aspen Meadows complex designed by Herbert Bayer. The Austrian émigré and consultant to Container Corporation of America, who had moved to Aspen in 1946, was there, dapper in his cravat, suntanned and still handsome at 70. Also sipping gimlets were other board members in charge of the IDCA: Saul Bass, the Los Angeles-based graphic designer; Eliot Noyes, design director at IBM and president of IDCA since 1965; and George Nelson, design director at the high-end office furniture firm Herman Miller. These men had been trained as artists and architects but had helped to define the American graphic and industrial design professions in the 1940s and 1950s. Their careers had flourished in the postwar period of economic expansion and were tied to the rise of a consumer society.

Meanwhile, in the meadow beyond this midsummer cocktail party for the cognoscenti of modernist American design, a very different scenario was taking shape. Milling about outside a big white concert tent, designed by Bayer, where the conference would be held, were student designers and architects, some of their young teachers, and a number of art and environmental action groups, many from Berkeley, California, who had made the 1,000-odd-mile journey to Colorado in chartered buses. With their waist-length hair, beards, open-necked shirts, bandanas and jean jackets, these groups signaled both their adherence to an alternative lifestyle and set of values (for which Berkeley was the unofficial American capital) and their distance from the largely East Coast conference organizers.

Among the groups arriving were members of the San Francisco media collective Ant Farm, who, by 1970, were well known for their advocacy of a nomadic lifestyle, their use of inflatable structures as the setting for free-form architectural performances, and their experiments with video as a vehicle for critique.

Since the theme of the conference this year was “Environment by Design,” several representatives of environmental action groups were also gathering, invited by Sim Van der Ryn, an assistant professor of architecture at the University of California, Berkeley, and founder of the Farallones Institute, a research center for studying environmentally sound building and design, and low-technology solutions to waste management.

Among those also invited by Van der Ryn were: Michael Doyle, founder of the Environmental Workshop in San Francisco; the People’s Architecture Group; Steve Baer, the Albuquerque solar energy enthusiast who founded Zomeworks and developed many of the housing structures for communes such as Drop City and Manara Nueva; and Cliff Humphrey, founder of Ecology Action, originator of the first drop-off recycling center in the US, whose Berkeley commune, known for smashing and burying cars, had just been featured in a New York Times magazine cover story. The cover image showed Humphrey pushing a bandaged globe in a baby stroller.

There was a third group, too, that was neither at the cocktail party nor among the festival-like gathering in the meadow. This group included Jean Baudrillard, the French philosopher and sociologist, and the architect Jean Aubert. They were members of Utopie, a Paris-based collective of thinkers and architects that, between 1966 and 1970, had been engaged in radical leftist critique.

Here were three very different tribes, each with its own design principles, conception of what the environment meant in relation to design, and critical methods. To the IDCA board, design was a problem-solving activity in the service of industry—albeit with roots in architecture and the fine arts. In the environmentalists’ and students’ view, designers needed to claim responsibility for the repercussions of their activities, and to understand design in terms of interconnected systems and natural resources. And the French group? Well, they objected to both conceptions, perceiving the gathering at Aspen to be a “Disneyland of Environment and Design” and, indeed, the “entire theory of Design and Environment” as constituting a “generalized Utopia … produced by a capitalist system that assumes the appearance of a second nature, in order to survive and perpetuate itself under the pretext of nature.” With such divergent worldviews and reference bases at play, and the prospect of a week in one another’s company, an ideological collision of some significance seemed likely.

Sure enough, as the June week wore on, tensions mounted between members of the American liberal design establishment and the eclectic assortment of environmentalists, design and architecture students on the one hand, and the French delegation on the other. The new arrivals to the conference were coming from very different places, both geographically and ideologically. But, in combination, their protests, which became evident during the event, targeted what the dissenters saw as the conference’s flimsy grasp of pressing environmental issues, its lack of political engagement, its hubristic belief in design’s power to solve social problems, and its outmoded nonparticipatory format.

The critique that materialized at the International Design Conference at Aspen in 1970 epitomized more widespread clashes that took place during the late 1960s and early 1970s between a counterculture and the dominant regime over issues such as the US government’s military intervention in Vietnam, the draft, and the civil rights movement. In terms of design discourse, the protests connected with broader challenges to modernist orthodoxies represented by the work of Italian radical architecture collectives such as Superstudio and UFO.

The ways in which critique was advanced were also under attack. The design establishment, represented by the conference organizers, favored consensus-building as a goal of discussion and a lecture format whereby speakers delivered long, nonvisual, prewritten papers from a raised stage to a seated audience. Dissenters at the conference, interested in participatory formats that could incorporate conflict and agonistic reflection, introduced theatrical performances, games, workshops, and happenings, and confronted the conference organizers directly with a series of resolutions they wanted attendees to vote on.

By favoring physical actions, and the spectacle of a public vote, the protestors at Aspen disrupted design criticism itself, which, in this period, was usually rendered public in its written form. They initiated numerous nonwritten, ephemeral elements, including corridor discussions, Q&A sessions, attire, body language and gestures, theatrical performances, inflatable structures, parties and picnics, objects, and graphic ephemera. These facets were recorded kaleidoscopically in photographs, a film, and audio recordings of presentations and discussions. In combination they represent a form of criticism as a spontaneous and performative event, which used countercultural activist tactics as a “style of action.”

The protestors were able to confront their targets in person, and could register the effects in real time. The multipronged internal critique of the conference led to a transformation of its content and structure not just in 1971, which saw the most emphatic demonstration of response and change, but also in subsequent conferences at least through the mid-1970s. As such, IDCA 1970 is emblematic of a disruption to, and a paradigm shift in, the established practice and role of design criticism in the postwar era.

Listen to the presentation on Spotify , Soundcloud, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, or Podbean