Thomas Karsten was a modern Dutch architect who lived and worked in the Dutch East Indies in the first half of the twentieth century. Most documentation relating to this period has been scattered or lost, which is why the publication ‘The Life and Work of Thomas Karsten’ is so timely and welcome.

Spread from the publication ‘The Life and Work of Thomas Karsten’

‘What to be deduced from the studies in this volume of Herman Thomas Karsten, architect, town planner, and intellectual? What is to be said about the legacy of this man who dedicated his life and skills to what he saw as the future of Indonesia?’ These two questions from the opening paragraph of the chapter entitled ‘Architect, town planner, and intellectual’, written by historians Joost Cote and Hugh O’Neill, summarize the aim of this critical project. The Life and Work of Thomas Karsten doesn’t just tell the story of a Dutch architect and his work. It dives deeper, unveiling the layers of complex and often unconventional ideas of the architect. The book comprises ten chapters. Eight of them are written by Cote or O’Neill, the book’s editor. The other two chapters are written by architecture historians Helen Ibbitson Jessup and Pauline K.M. van Roosmalen.

Before discussing the book, I think some historical context is necessary to underscore its importance. After the promulgation of the Ethical Policy in 1901 by Queen Wilhelmina, in which the Netherlands accepted ethical responsibility for the welfare of its colonial subjects, the landscape of building practice changed. The policy set a blueprint for the Dutch East Indies for the first time since its colonization in around 1600. Taking advantage of the liberal economy initiated in 1870 by the introduction of the Agrarian Act, many construction projects were developed in the Dutch East Indies.

These projects attracted many young Dutch architects to the colony. For them, they offered an excellent opportunity to realize their architectural ambitions. Pauline K.M. van Roosmalen accurately depicts this spirit as ‘a new sense of social responsibility, and in tune with the aesthetic and perspectives of the new cultural and social movements then sweeping Europe, they came inspired to introduce the latest modern ideas and approaches to the practice of architecture and urban reform’. That said, there were many profound discussions, experiments and designs between 1900 and 1948 in the field of architecture in the Dutch East Indies. Unfortunately, much documentation from this period has since been scattered or lost.

Spread from the publication ‘The Life and Work of Thomas Karsten’

This book contributes to the study of work by Dutch architects in the early part of the twentieth century in the Dutch Indies. The three parts of the book discuss different aspects of the story of the life and work of Thomas Karsten (1884-1945). Part one offers an overview of his life, in particular his relationship with his family. In the second text, entitled ‘Education and Inspiration’, Cote discusses Karsten’s years in Delft and Berlin. Historical sources from this period are limited. Cote frequently cites from Marinus Jan Granpré Molière’s diary to paint a picture of Karsten’s student life in Delft. Yet his Berlin period is even vaguer. Two articles that Karsten published in Berlin, ‘Berlijnse Indrukken’ (1911) and ‘Over de Deutschland Werkbund’ (1912), are the only significant records from this time. Nevertheless, these articles provide fundamental insight into his thinking and later direction in the Dutch East Indies.

The second part of the book focuses on Karsten’s ideas and work. Five texts unfold various layers of his thinking. ‘Defining a Cultural Blueprint’ by Cote and ‘The Architect at Work’ and ‘Architecture of Commitment’ by O’Neill examine his contribution to architectural discourse, especially his ideas on appropriating indigenous Javanese culture. Married to a Javanese woman, Karsten had an affection for the culture that went beyond pragmatic intentions. He agreed with H.P. Berlage that Javanese culture and craftsmanship was a valuable resource in defining a new architecture for the Indies. Based on this conviction, he founded the Java Instituut in 1918, whose aim was to reinterpret Javanese culture to fit the ‘modern world’.

Karsten was an avid writer. Cote divides his writing into three periods to help explain the development of his thought. First, his texts about Javanese culture and his observations from his first visit to Europe (1920-1921), published in De Taak (1917-1923). Second, his writing about conferences and activities organized by the Java Instituut, published in the organization’s official journal, Djawa (1921-1940). And third, articles written after his second European trip and his travels to America, Japan and the Philippines in 1930-1931, which were published in Locale Belangen, a monthly publication from the Vereeniging voor Locale Belangen (‘Association of Local Interests’).

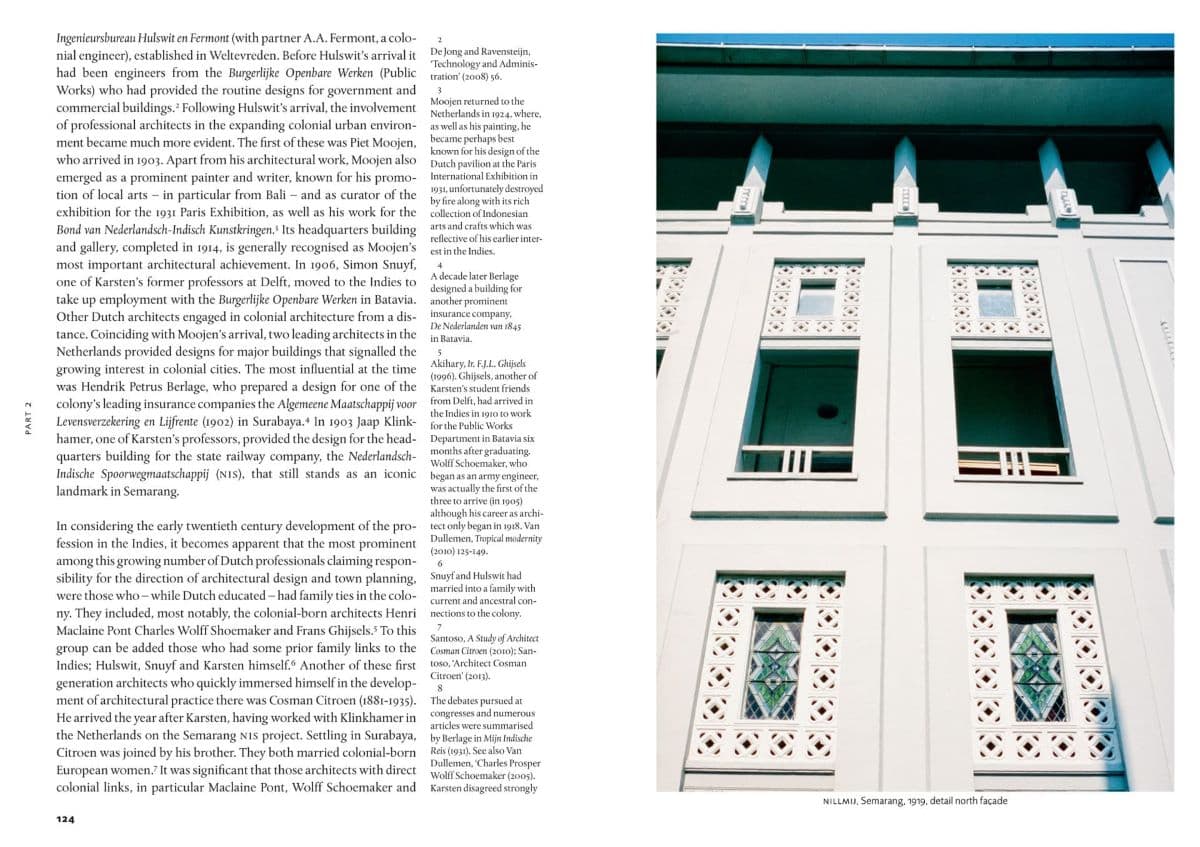

It is interesting to follow the evolution of Karsten’s ideas about Javanese culture and design. From merely practical elements such as the shading devices in the building for the Nederlandsch-Indische Levensverzekering en Lijfrente Maatschappij (NILLMIJ) in Semarang (1919) to his mimetic approach in the Sobokarti Theatre (1929) and Zustermaatschappijen building (1930). In his Johar market building (1938) in Semarang and Jati Langeh market building (1938) in Solo, references to Javanese architecture are not simply about form but also space and ambience.

The final two texts in the publication underscore two milestones in Karsten’s career. In the essay ‘H.H. Mangkunegoro VII and the Search for a Modern Javanese Architecture’, Helen Ibbitson Jessup discusses the unique relationship between Karsten and the Javanese prince Prang Wedono (later Mangkunegoro VII). The project commissioned by the prince to renovate the Pendopo Agung (Royal Hall) of the Mangkunegaran court provoked debate about modernity in Javanese architecture. The prince, who later became Karsten’s patron, wanted to incorporate European features in his court. His experience living in Europe had exposed him to hospitals, offices, warehouses and so on that did not exist in Javanese culture. However, throughout the project, Karsten positioned himself as the guardian of Javanese culture. Using the correspondence between the architect and Mangkunegara VII as his primary source, Jessup brings us to the heart of this exchange of ideas, and opens up a discussion about the incorporation of Javanese tradition into the architecture of the Netherlands Indies.

But the best-known work by Karsten in the Dutch East Indies is not architecture but urban planning. In ‘Modern Indisch Town Planning’, Pauline K.M. van Roosmalen concludes that he essentially initiated this field in the Dutch East Indies. Entitled ‘Indies Stedebouw’, his work about Dutch East Indies Town Planning is his most important contribution to the area. Roosmalen discusses the impact of his work not only on town planning in the Dutch East Indies but also on urban planning after Indonesia gained independence.

Before the publication of ‘Indies Stedebouw’, there were no guidelines or discussions about urban planning. In fact, the field was even considered new in the Netherlands. The Technische Hoogeschool in Delft only added urban planning to the curriculum in 1905, and Karsten was among the first students to study this new subject. The importance of ‘Indies Stedebouw’ also indicates the development of the practice and regulation of urban planning in Indonesia. These guidelines influenced many early masterplans for Indonesian cities after Independence.

Part three of the book offers concluding remarks. If the writing of Cote and O’ Neill in ‘Architect, Town Planner and Intellectual’ offers an assessment of Karsten’s journey as an architect and urban planner, the real ending is Cote’s text ‘Architect of an Idealist World’. Karsten’s period of internment in Japan was a moment of reflection. ‘De Eenheid der Wereld’ (‘The Unity of the World‘), the title of a document he wrote during this period, brings his ideological journey full circle. As if it was written in response to his earlier texts ‘Over de Deutschland Werkbund’ (1912) and ‘Rassenwaan en Rassenbewutstzijn’ (1918), about the communal cooperative movement and freedom in a colonial context, the document transcends these thoughts into spiritual ideology, as described in Karsten’s words:

“Being part of a collective in a material and spiritual sense, develops within and [is] sheltered by the society’s abundant nature, created by ancestors and the group, developed further by himself and his friends, making their individuality count within the unity.”

“The oneness of a Community exists beyond the freedom of lesser communities and individuals; freedom exists but only within the Unity: valuable: seeking the essential bondedness with his nature.”

The words are a beautiful final reflection on Karsten’s architecture of humanity ideology, where culture, social life and architecture are seamlessly interwoven to reach the ultimate goal: an unsegregated community.

That concluded his journey. Just before he died on 21 April 1945 in Cimahi Hospital, Karsten offered his final thoughts on a topic that was always core main interest: creating an environment where people, regardless their differences, can co-exist harmoniously.

This book is important for anybody interested in the history of modern architecture in the Netherlands Indies. It paints an excellent picture of the life and work of the architect and offers a wealth of historical material and information for further discussion and research. Such a contribution opens up many new possibilities to study design methods and urban planning experiments in the twentieth century in the Dutch East Indies. The book also reveals many layers of complexity, especially in the period of post-ethical policy. The story of colonialization in the archipelago is not merely about the struggle of Dutch and local people. It is a stage on which the cross-appropriation of dreams, ideology and identity among a vast range of people takes place. The life and work of Karsten teaches us that colonization in the Dutch East Indies is never direct and simple.