The Arzobispo River in Bogotá has become a polluted creek. Silvia Leone (TU Delft) aims to give the river back to the residents of the surrounding neighbourhoods. She designed a park over a length of one kilometre in which nine pavilions are projected to serve the neighbourhoods and made a beautiful film about it.

Sólido Líquido Lítico – aerial view of the bath

Can you explain your choice of subject?

The inspiration for this project came from a fortuitous encounter with a book on the indigenous legends of Bogotá, which identified the river Arzobispo, in the neighbourhood of Teusaquillo, as a historical location for sacred baths. Today the river is a polluted creek working as a traffic lane in between gated urban blocks. Bogotá is a complex and very heterogeneous city, with fragile social and political dynamics. I thought it was important first of all to accept this multiplicity and realised that architecture alone, or rather one building only, would not be able to formulate a convincing proposal in this context. Only an integrated approach of urban, landscape and architectural design could be a wise strategy for the recuperation of the natural environment along with the re-connection to the community.

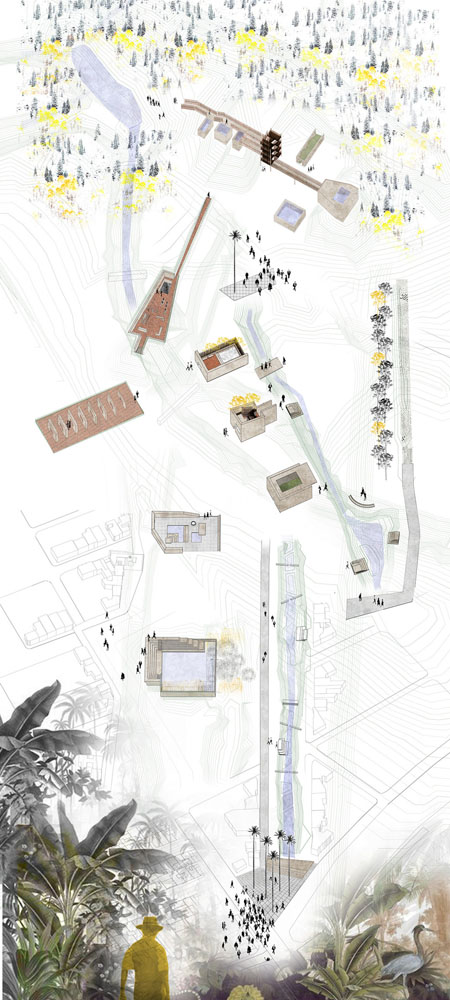

Bogotá’s water courses, the Arzobispo River and the one-kilometre-long river garden

What or who are your sources of inspiration and can explain this?

I believe it is important to feed our mind with as many varied stimuli as possible. Cinema is for me a great source of visual inspiration when it comes to atmospheres and experiential design. Also literature and certain writers specifically are able to arouse very striking images. I believe that the imaginative power that is exercised when reading was a very useful precedent for me to the practice of architecture. Also, an interest in the making and ”know-how” of architecture can be a very fruitful source of creativity.

State the key moment in your graduation project.

The graduation year has been an intense year dotted with many key events on the professional and personal side. As for everything in life, I believe all contributes to the final result. First to mention is the 1 month long trip to Colombia, which was an essential starting point. The workshop with Bogotan students at Universidad de Los Andes was a rare opportunity to discover the city in depth. Another key moment was a long period of self study, where I could think, sketch, design freely and be my most creative, trying to push the project to its limits.

an imaginary discovery of the river garden, connecting mountain and city, wild and tamed

Project text

The design proposal comprises three levels of intervention. First, there is the urban-ecological scale to restore the natural biotope of the polluted river. Then there is the landscape design to articulate the garden and its zones. Lastly, there is the architectural design to create the pavilions and the infrastructure that is to embed the revitalized landscape in its setting.

To reinstate the natural biotope, it was necessary to remove the layer of concrete from the river bed and restore the underlying natural soil by digging and levelling. This act of excavation is part of the concept underlying the pavilions, with furrows drawn through the ground and through the dense blocks. This brings to light the elements of water and soil by exposing them in the urban context but also by revealing them at unexpected places.

The architecture of the neighbourhood rooms is designed to interact with the landscape. The light infrastructure developed for this purpose provides access, enclosure or contact, while simultaneously offering alternative forms of multi-functional public space. The rooms engage in dialogue with their immediate context, their architecture transforming along the river garden. From an expression of surface, floor, wall and enclosure, the architecture gradually fades, as a door and a series of columns, until it reveals its structure and dissolves into the landscape.

Architecture attains a ‘lithic’ state, reduced to its most basic function, a mass sculpted by time and use. To unearth also means to reveal and experience what is lying beneath or behind. The physical excavation of the soil suggests that it is exposing what the river once meant to the city while at the same time dictating its new future. It generates a cycle of sensorial appropriation of nature, memory and collective responsibility. The river garden becomes an encounter between untamed and domesticated, primal and civilized, mountain and city. It is a place for the discovery and regeneration of both the natural and the human environment.

the bath and the hollow ground

Silvia Leone, contact

school/discipline

TU Delft Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment / Architecture

graduation started

September 2018

graduated

July 2019

What are you doing now?

I am working as an architect at WAM Architecten in Delft. I also continue researching with workshops and small projects.

What hope / do you want to achieve as a designer in the near and / or the distant future?

I was drawn to architecture by the fascination of translating the raw and haptic world of materials into an experience, able to shape people’s thoughts and actions. What is most moving for me is to think that people will remember important moments of their lives in combination to a place – the school they went, their first house… I want to be the creative mind behind those memories. My hope as a designer is to see architecture grow outside of the logics of fashion and mass production and welcome more room for experimentation and unconventional thoughts into its daily practice.